The eighteenth century was an age of elegance. Never in European history do we see men and women so elaborately artificial, so far removed from natural appearance. What could not be done with the natural hair was made with wigs. This epoch was an extravagant explosion of amazing hairstyles, a reaction completely opposed to the modesty and shyness of former centuries. The hair was in synchrony with the "Rococo" style, which was the most important one until the end of the century. It was an artistic style in which curves "s" shaped predominated, with asymmetries, emphasizing the contrast; a dynamic and brilliant style, where the forms played integrating a harmonious and elegant movement. A style according with an age of new philosophic ideas, like the Enlightenment, and according with the affluence of a powerful economic wealth arrived to Europe from the travels to the new continent, America. New social orders started to born; besides of the clergy and the nobility, a strong bourgeoisie of nouveau riche people appeared, who make fortune and was positioned into the best of the social and political spheres, imitating in all their costumes to the nobles. A style according with a time when the science was more independent of the religion, reaching spectacular achievements and developing, in consequence, a technology which would open the doors to the Industrial Revolution. People at that time believed that they were living in the best of all possible worlds. At the end of the century, artistic and cultural styles changed; it appeared the "neo-classic" style, much more sober and conservative, with a return to the classic Greek and Roman esthetic.

The wear of wigs in men started to be very popular at the end of the 17th century, while the reign in France of Louis XIV, the Sun King. All his court began to use wigs, and as France was the pattern of the fashion for all Europe at that age, the use of wigs was spread to the rest of the courts of the continent. In 1680 Luis XIV had 40 wigmakers designing his wigs at the court of Versailles.

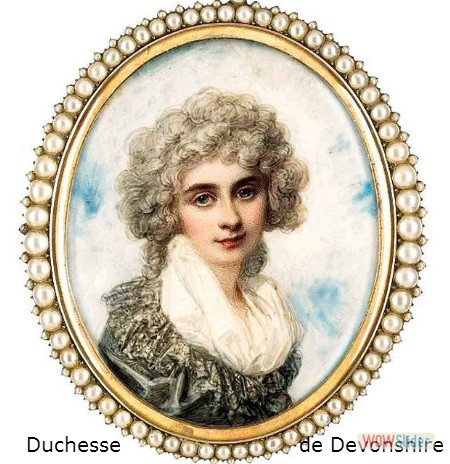

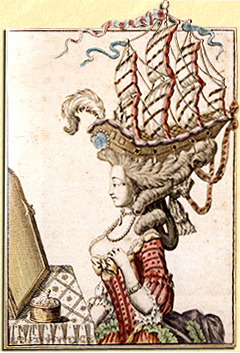

From 1770, wigs were also extended to women. And, as the years were going on, women wigs were being made taller and more sophisticated, especially in France. Men's wigs were generally white, and women's wigs of pastel colors, like pink, light violet or blue. Depending on how wigs were ornamented, they could reveal a person's profession or social status. Wealthier people could cost expensive wig designers and better materials. They were made in general with human hair, but also with hair from horses or goats. The countess of Matignon, in France, paid to the famous hairdresser Baulard 24.000 livres a year to make her new headdresses every day of the week.

Near 1715, wigs started to be powdered. Families had special rooms for "toilette", where they arranged and powdered their artificial hair. Wigs were powdered with starch or Cyprus powder. To powder wigs, people used special dressing gowns, and covered their faces with a cone of thick paper.

ROBBERY OF PERIWIGS IN THE STREET

At the beginning of the century, men hairstyles were more elaborated than women's. Still was in fashion the "Louis XIV style", with great curls and the hair shoulder-length. At the end of the century, the trend is reversed: women used towering masses of hair, rising 1 or more feet above the head. These wigs had some inconveniences: door frames should be elevated for they could pass through, and sometimes the pressure of heavy wigs on their heads caused serious inflammations on their temples.

At the middle of the century, the new king of France, Louis XV, imposed a smaller wig's style for men and the strictly white or grayish powdered hair. Men also wore since the middle of the century a single ponytail on the nape, tied with a bow, a very popular style in every European court at that time. Women continued with their extravagant styles until the French Revolution, when all the luxury and exuberance were vanished into the new republican ideas. Since then, hairstyles were more classic and simples.

"FONTANGE" HAIRSTYLE

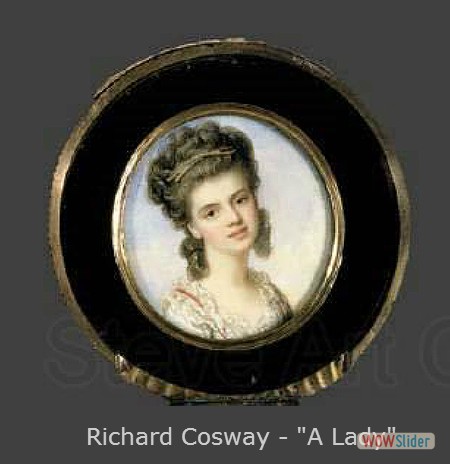

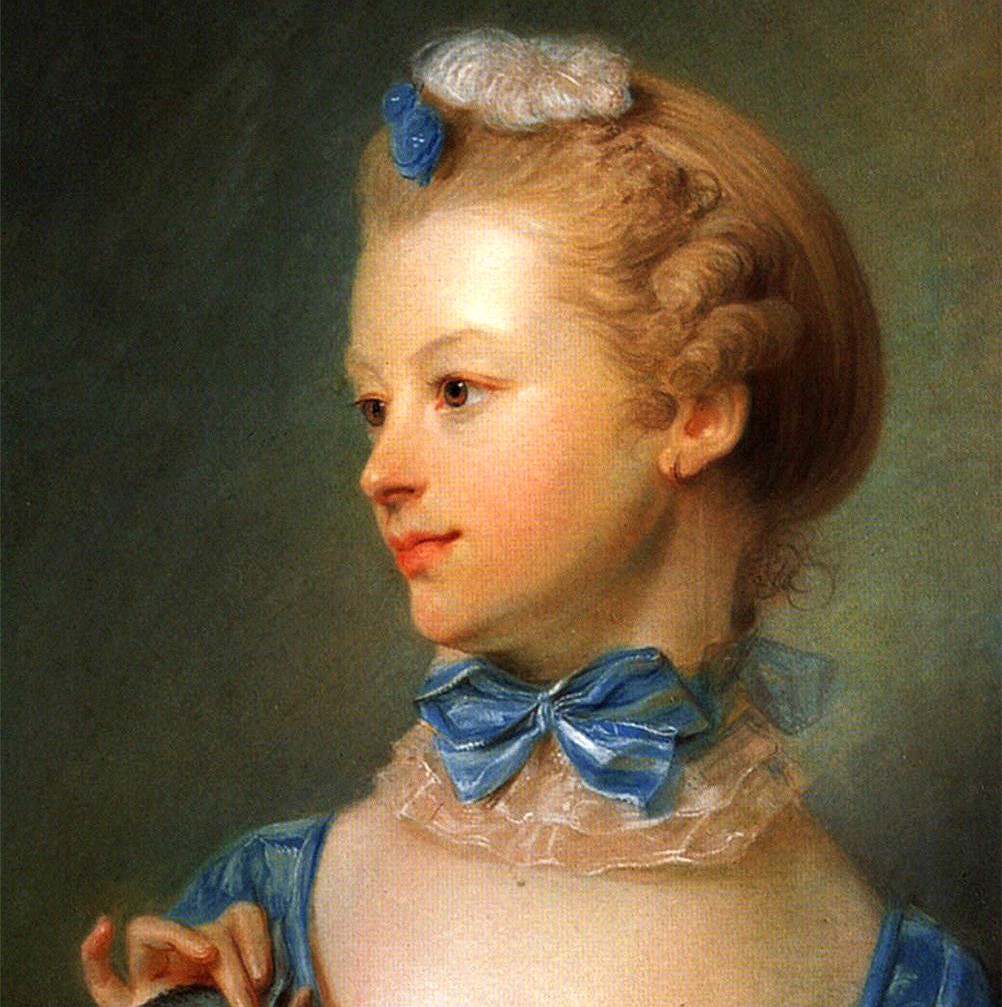

Under the reign of Louis XV costumes changed and women's hairstyles became simpler. It was in fashion a hairstyle called "tête de mouton" (sheep head), with short curls and some locks on the nape. Women didn't wear wigs until 1770. Since then, hairstyles became more elaborated.

WOMEN HAIRSTYLES AT THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY:

MEN HAIRSTYLES AT THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY:

NEW HAIRSTYLES AFTER THE FRENCH REVOLUTION:

Philosophic changes, changes of the way of thinking, changed also the hairstyles. Little by little, people stopped to wear wigs, and the hair started to be natural, with no powder. The Revolution and the transformation of the whole system happened suddenly -although it was, in many ways, expected- by a legislative coup of the deputies of the bourgeoisie with the back up of part of the clergy and the nobility, but it was not that fast. All the images we can see today of Robespierre and Danton, chief leaders of the Revolution, show them with powdered wigs, until their death in the guillotine. Jean Paul Marat, however, the other revolutionary leader, already wore the new esthetic. And one of the principal men of the Revolution, the painter Jacques Louis David, was already absolutely inserted in the neo-classic style, in his works and in his personal appearance. As the neo-classicism became more popular, hairstyles changed. At the arrival of Napoleon Bonaparte, very few people wore wigs; the Empire style shows all the politicians with their natural hair, combed in an informal way, symbol of a new age of independent thought. Military delayed more time in abandoning the old hairstyles, but in the Napoleon army all of them looked a natural hair. Women, at the end of the Revolution, stopped to use high and complicated hairstyles and wore their hair natural, with no powder, held with tortoise shell combs, pins, or ribbons, instead of elaborate ornaments.

Perhaps, the first people who stopped to use the old style of powdered wigs and much elaborated hairstyles, were, paradoxically, the same aristocrats who formerly started to spread around that fashion. Because of the fear of being recognized, and, furtherly imprisoned and guillotined during the Robespierre’s Reign of Terror (1790-1793) they went out of their houses with plain and simple clothes, and with natural haircuts; with no wigs, short hair, not covered, and, as too much, wearing coiffures of neo-classic style. In fact, they didn’t have too much opportunity to use the old hairstyles; at that time, in all European countries, styles and costumes also had changed. The Romantic Age, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, started with a completely different fashion.

__________________________